Most journalism uses words to describe events sometimes accompanied by images to help readers get the full picture.

Graphic journalists have turned things on their head. They primarily use images to tell the story, and words play second fiddle. Most of us are familiar with ‘comics’; stories in pictures such as The Beano, or The Adventures of Asterix and Obelix. The difference is that Graphic Journalism deals in real facts. Sometimes it’s also referred to as comics journalism, illustrated journalism, visual reportage or nonfiction cartooning.

In this type of journalism the storytelling would be incomplete without the illustrations. One such journalist is Joe Sacco whose stories have travelled the world. Joe’s work in journalism started with visits to war zones such as Bosnia, and telling people’s stories through cartoons. We follow his adventures because Joe draws himself into the story. This gives him the opportunity to tell the story in a more personal way. He meets both the good and the bad and leaves it to us to decide who is who.

After studying Journalism at the University of Oregon in the USA, Joe found it hard to find jobs telling the stories he was most interested in. He found himself doing the thing he enjoyed most, drawing cartoons. He started with romantic comics (Eww!) and then worked for a while on satirical comics (that’s funny and critical at the same time) - Joe even published his own comics magazine for some time.

Joe’s travels inspired him to report on the problems between Palestine and Israel in his first journalistic graphic book Palestine. He drew a collection of stories which he then put together in a book which sold more than 30,000 copies in Britain alone. Gattaldo met Joe to ask him a few questions.

Mr Joe Sacco

A. I studied journalism but I’ve been drawing since I was a kid and simply never stopped. So, yes, you could say I’m self-taught.

A. I started out doing stories about my life so when I first travelled to the Middle East. I thought I’d just illustrate my adventures. But while I was there my journalistic training kicked in and the work became more focused on interviews and gathering information.

I kept myself as a character without thinking too much about it. Now I realise that including my character is a way of signalling to the reader that they are seeing things from my perspective and that’s not the standard journalistic way of going about things.

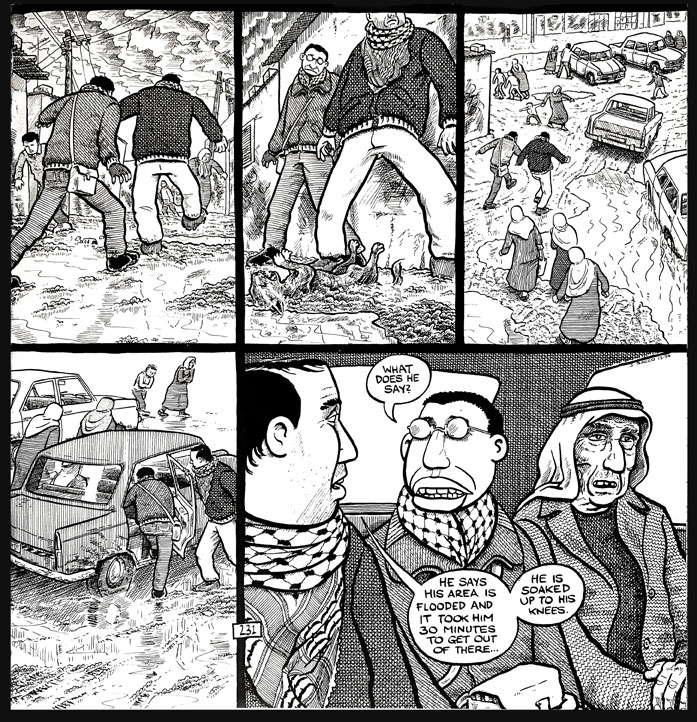

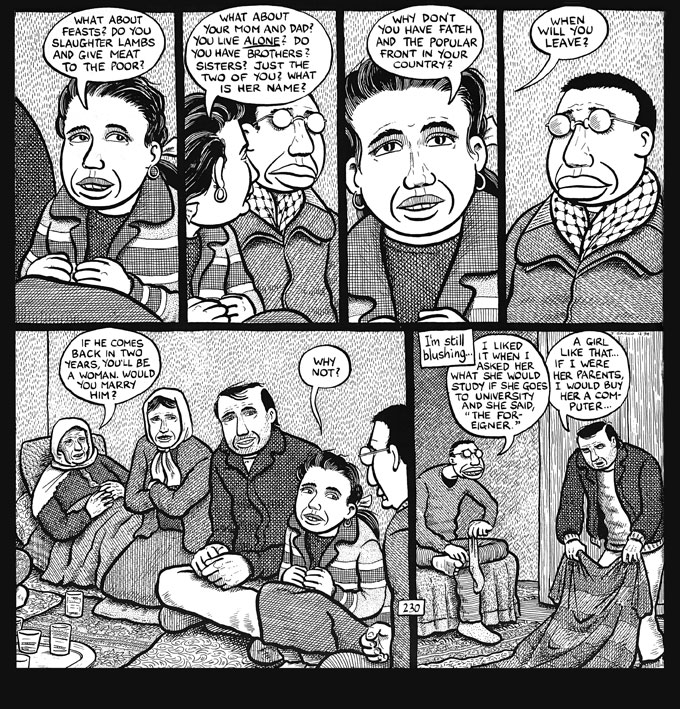

Detail from Joe Sacco's book 'Palestine', published in 2009

A. I read all I can about a subject. But you always learn ten times more when you’re actually there.

A. I’m as careful as I can be. I’m not a particularly courageous person, as those closest to me can tell you. I stick with guides who know the conditions on the ground and they’re usually good about keeping us safe.

A. I enjoy talking to people and I like to listen to their stories, and perhaps they pick up on that. The great secret to journalism is that people like being asked about themselves so you just have to give them the space to speak.

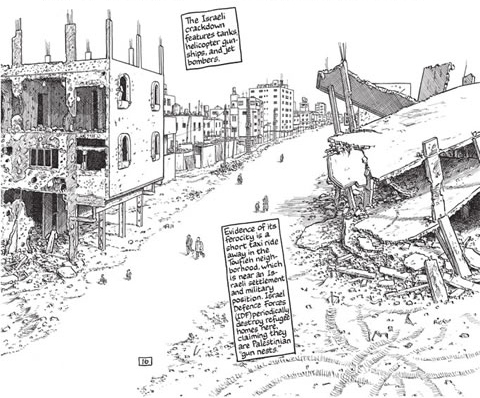

"I’m as careful as I can be. I’m not a particularly courageous person, as those closest to me can tell you." - A scene of war devastation in Joe Sacco's book 'Footnotes in Gaza'

A. Yes, it can be hard for people to talk about their difficult experiences. I never push people to continue, and if I see someone is becoming uncomfortable, I always give them the option of stopping. But usually they want to overcome their emotion and tell the story anyway.

A. I don’t think the romance comics had much influence, but certainly the satire showed that I always had an intentional point to make.

A. I don’t try to think about that too much. Some people have told me they’ve learned something from my work so I do think individuals can change what they think based on what they read. But I don’t necessarily think I can change the world. I think of myself as chronicling (recording) my times.

A. The journalist that most inspired me is George Orwell because I feel he had integrity. My biggest influences in art are Pieter Bruegel the Elder, whose Flemish paintings from the 1500s open up a window into his world, and Robert Crumb, the American underground cartoonist who makes even inanimate objects like a cup or a lamp seem to jump off the page.

Detail from Joe Sacco's book 'Palestine', published in 2009

This interview first appeared on Plucky, the paper for inquisitive kids